Managing your relationship through the pandemic

I wrote this a little while ago in the middle of all the lockdowns, while I worked through Skype, Zoom, WhatsApp, Messenger, telephone and any other medium my clients wanted to use. In the next room was my partner also at home working online. Our 12 year old son filled the vacuum with his squealing laughter and the constant screeching of his chair as he got up and down to gesticulate to his computer screen while embarking on virtual adventures with his mates.

Our house had taken on a kind of horizontal divide: we dressed formally from the waist up, boardshorts and tracky-daks below the camera line. Our manicured Skype backgrounds belied the pile of unfolded laundry just out of view on the floor, expanding according to its own exponential growth curve.

I’m a relationship counsellor and I have struggled as much as anyone during this pandemic. But I have some ideas about how to get through this pandemic crisis with your partner.

Togetherness Vs Separateness

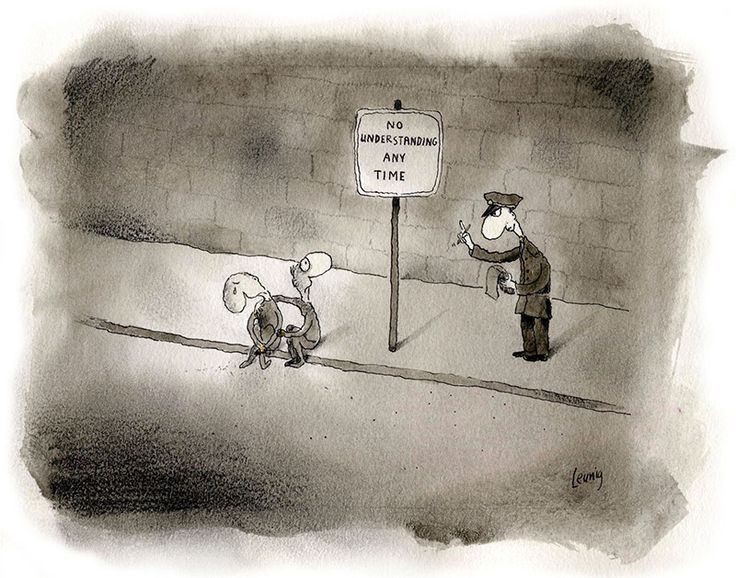

The balance of these two states is probably the core tension of any long term relationship. But things are ratcheted up when you are confined to each other’s company like this. And besides, the general stress and uncertainty facing all of us keeps us close to our stress limit, more easily tipping us over into aggression or withdrawal.

Even in normal times couples usually have one person who seeks closeness more than the other. This tendency often triggers feelings of pressure in their partner, resulting in their seeking more separateness. They might even tell their partner they are needy or selfish for wanting closeness and dismiss their needs as inappropriate, or worse, as childish. Of course, such responses just reinforce the first person’s need for closeness, starting a vicious cycle of one partner feeling increasingly disappointed and the other feeling pressured and burdened.

These roles might change within the couple or they might become assigned consistently to one person. Most couples resolve this dynamic well enough for enough of the time. But there is always some degree of tension that can spill out into conflict.

Togetherness needs can manifest as a need to be listened to, a need to be touched, or affirmed, to be defended by their partner in some conflict, to go out and do something together, or a need to have their partner do something to help (such as the cleaning, or pay your bills, or find your socks). Sex often turns into a togetherness need – often men need sex in order to feel loved in their relationship, often women need to feel loved in order to engage in sex.

Separateness needs can manifest in things like wanting to have time away or with your friends, or in your shed, or watching your own netflix show away from the reactions and judgements of your partner. Just burying your head in a good book can feel like an escape from the demands and expectations of your partner or children or of the world in general. It can manifest as a reaction to your partner’s togetherness needs. The more we feel our partner needs us, the more we value separateness.

And of course, we often get very upset and grumpy about how our partner is pushing back on our need- whether we are wanting togetherness or separateness. Partners can sometimes lash out verbally, telling their loved one how unreasonable the other person is, or what a bad partner they are for not meeting their own need.

Inane and petty arguments are often just proxy wars for this conflict. For example, Bruce might complain at Jenny for never keeping the lounge room clean. (The reason he says this with anger is that he feels Jenny doesn’t care enough about him and his need for having things in order – a togetherness struggle). Jenny on the other hand dismisses him and tells him that she is not his slave and that he should just do it himself if it bothers him that much (a struggle for separateness).

Darren complains that he and Jenny haven’t had sex for three weeks. (He feels a nagging sense of rejection, of not mattering to her – a togetherness need). Jenny snaps back, “How am I suppose to feel like having sex when you’re always nagging me and pressuring me about it? It’s not a turn on!” (She feels burdened and pressured. Her body stiffens when Darren touches her as if she has to protect herself from intrusion – a need for separateness).

Because we are often cooped up like battery hens right now, this struggle is far more immediate – it’s in our faces. The person who struggles for togetherness feels the tuning out of their partner more acutely than ever before. The person who struggles for separateness feels the togetherness needs of their partner more heavily and feels their urgency and expectation. Meanwhile the tension simmers.

Here’s a path forward:-

- Accept the difference between each other and stop dismissing or pathologizing your partner over their particular need. It’s these types of differences that attracted you to each other in the first place.

- If you are the one who often seeks togetherness, ration it out. Stop the pressure. Accept the fact that your partner feels pressure and stress whenever you feel an urgency about your need for togetherness. If you do, you won’t interpret their pulling back as a rejection but rather as a coping behaviour.

For example, Nick might learn to accept that his wife, Ruby, doesn’t need as much touch as he does. He might even recognise that she can instinctively pull back from it if it feels intrusive or demanding to her. Instead of taking it as some personal rejection of him as a partner, he might see it as her difference around touch and affection. He might decide that rather than asking for hugs like a gambler throwing coins into a poker machine, to instead hold it back, and spend some time meeting her need for love (maybe she likes to sit together sharing what has happened in her day). He might then say how much he’d like a hug from her and invite her into his arms. (Remembering it is an invitation and not a demand, Nick doesn’t interpret her avoiding or baulking as a rejection. Instead he sees she is just full of stress or other preoccupations and knows he can try again later with more success later.)

- If you are the one who struggles for separateness – compromise. Meet two togetherness needs of your partner, then assert one separateness need for yourself. Keep this 2:1 ratio up every day.

For example, Nick might learn to accept that his wife, Ruby, doesn’t need as much touch as he does. He might even recognise that she can instinctively pull back from it if it feels intrusive or demanding to her. Instead of taking it as some personal rejection of him as a partner, he might see it as her difference around touch and affection. He might decide that rather than asking for hugs like a gambler throwing coins into a poker machine, to instead hold it back, and spend some time meeting her need for love (maybe she likes to sit together sharing what has happened in her day). He might then say how much he’d like a hug from her and invite her into his arms. (Remembering it is an invitation and not a demand, Nick doesn’t interpret her avoiding or baulking as a rejection. Instead he sees she is just full of stress or other preoccupations and knows he can try again later with more success later.)

- Always make the benign interpretation for your partner’s behaviour. Couples are always getting into trouble because they assign the most hurtful meaning they can to their partner’s behaviour.

For example, Bruce always feels that Jenny ignores his need for tidiness and order because she just doesn’t care enough. She might even say she doesn’t care about his demand during a fight, but that doesn’t mean it’s true. Jenny pushes back like that because it is the only way she knows to assert her sense of control over herself and to block intrusive demands from important others. She learned this as an adolescent to create her own privacy with a mother that constantly interrogated her about school and friends. If Bruce recognises the deep psychological threat she feels when he is grumpy about housework he wouldn’t interpret it as her not caring. He might instead find other ways of negotiating and compromising with a much softer start up.

Jenny also could look past the controlling overbearing male she sees when Bruce complains. She might accept that mess actually does raise his anxiety and makes him feel deeply uncomfortable. She might learn that she doesn’t have to cut him off to meet her need for personal sovereignty. Instead she could practice different responses that contain a mixture of boundaries and empathy. Eg. “I know how you feel about the lounge room. I tell you what, I’ll have a shower and then pick up the things that belong to me. I’m too frazzled from work to do anything more at the moment.”

If all of these couples could work equally hard at their own contributions to their relationship problem, they might just make it through this crazy time.